We ask fish expert Jonathan Balcombe all about fishes, flies and his favourite facts

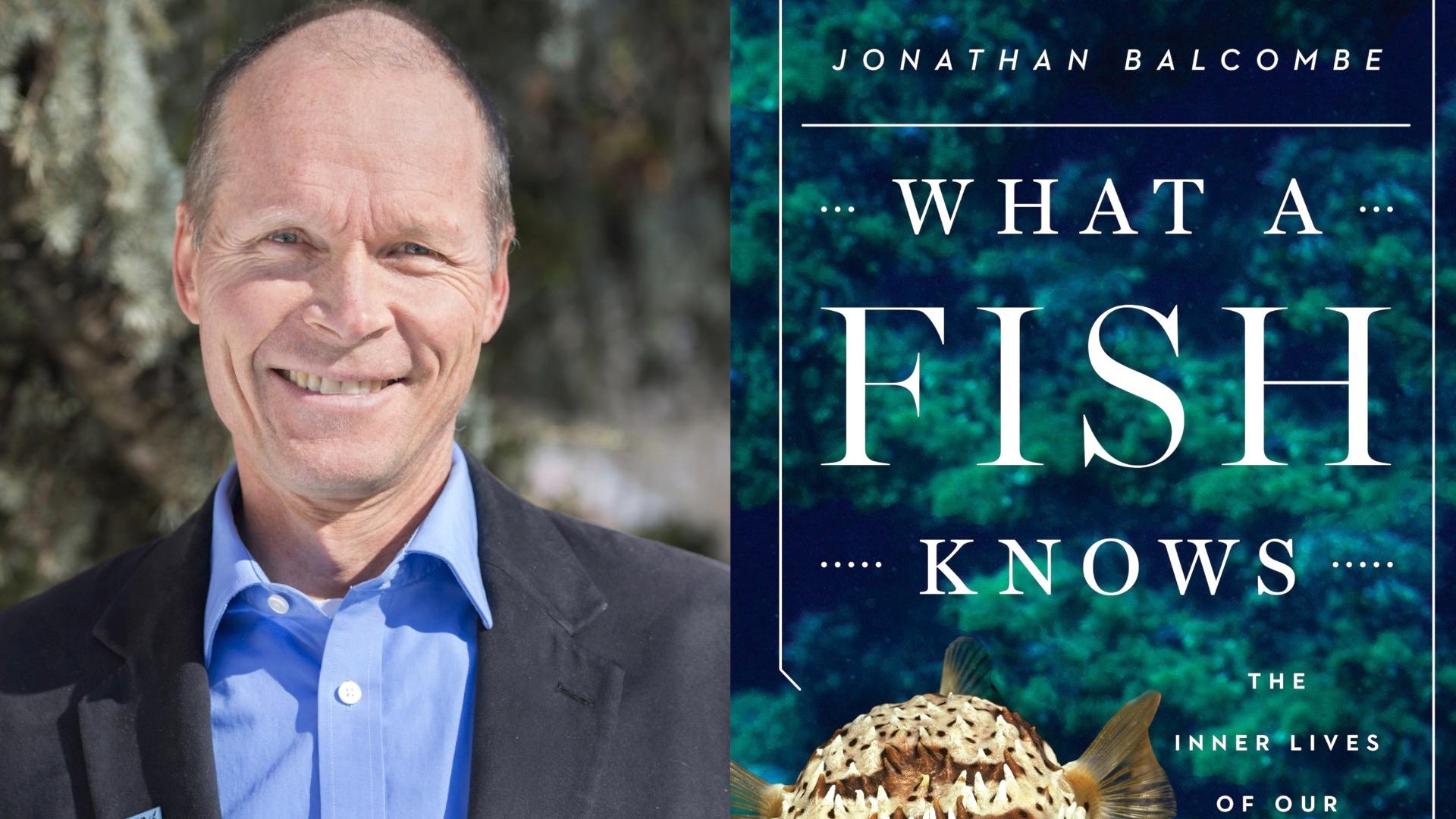

Author of What a Fish Knows, Jonathan Balcombe certainly has a few fishy stories up his sleeve. With the publication of his new book, Super Fly, we ask him all about fishes, flies, and why they are so important.

Full video transcript

1. Your work challenges human perceptions of animals. Have you always seen things differently to others?

Yeah, I've always felt my views on animals are not the norm. They don’t fit squarely in the middle of the average. I think back to my childhood and I would feel quite alienated from little kids who squashed insects under their feet. In fact, I felt they were more alien to me than the little creature that they are killing.

I think a lot of that is learned behaviours, it’s culture. They probably learn that from their parents who maybe didn't like insects and were vocal about that and harmed them or poisoned them or whatever. So much of it is what we learnt from adults. If they has seen their parents care about them or remove them and take them outside and treat them compassionately then I think they pick up on their behaviour.

We’re kind of products of our upbringing so that’s important to keep that in mind. You know I often wonder what would my attitude to animals be like if I was raised in a family that exploited and abused animals all the time. I wasn't - my family was very interested and respectful of life.

Although I do think tonight I was born with a gene for caring about animals, I just feel like it's very intrinsic to who I am. I think anyone today who’s vegan probably feels like an outlier and they don't feel like they’re wrong. We vegans tend to be righteous internally, hopefully not too righteous externally.

We know we're making the right decision by not consuming animal products but we’re not exactly the centre, we’re not exactly typical in that way. So I think those who really care about animals do kind of carry that awareness that they're not completely fitting in and it's not a case of how should I fit in better, it's like when are they going to catch up to me.

2. What is your favourite fact about fishes?

There's so many to try to choose from but one that sticks out to me is a study that was done by researchers at the University of Lisbon.

If I can condense, the conclusion is that fishes who are caressed will seek caresses to relieve stress. So they stressed these fishes, they got these surgeonfish, about 32 of them, from the Great Barrier Reef. Being caught taking out of your home is pretty stressful to begin with and you can measure that by taking a little blood sample and measuring cortisol, a stress hormone. It was very high levels and then they stressed them more.

By the way just a disclaimer here - I don't necessarily endorse these studies because I describe them but the fact that they have been done, if that information can change attitudes about these creatures then I will use that information unabashedly.

So they stressed them further by taking each fish and putting them in a shallow bucket of water for half an hour and that's going to be very stressful, just as it would be for us in an analogous situation.

And so once again they measured stress levels and they were very stressed and then they divided them into two groups and each fish was put into a tank of water individually, with plenty of water this time, with a model of the cleaner wrasse, a very realistic model. This is a fish that does cleaning services on reefs. That’s a whole other symbiosis that’s fascinating and sometimes the little wrasse will actually caress against the skin of the client fish probably to make them feel good about the treatment they’re getting and want to come back because it's their likelihood, it's a business relationship between these fish.

So what they did in this study the model fish was either in one or two conditions; it was stationary so it didn't move or it was hooked up to a motor that caused it to go in a sweeping motion back and forth so it could deliver caresses. And the fishes in this one with the moving model would swim up to it and get caressed. They counted how many times an hour they did this and it was about 15 times an hour they’d spend several seconds or maybe half a minute up against model getting caressed. And their stress levels came markedly down in that condition. The ones in the stationery model where there was no moment and therefore no opportunity to receive caresses they made 0 movements. I mean a striking difference - 15 times an hour, almost addictive behaviour, and 0 times an hour. Needless to say that second group their stress levels did not drop.

So to me, that is a mind-blowing study, a mind-blowing finding that totally blows out of the water the old assumption we have about fishes is that they are cold-blooded, unthinking, unfeeling creatures. There are so many ramifications to that one study.

I'm happy to say that at the end of the study the all of the surgeonfishes survived the study and the researchers returned them to their initial home on the reef and they report that in the paper. That I was very pleased to see. It’s becoming more common for scientists to report the final disposition of the animals in their studies but it’s still not typical. It’s an important part of the paper to not only do that but to report it.

So we can summarise that by just saying in human terms, we know a massage feels good to us, it destresses us, and the same thing occurs for fishes.

3. What are your thoughts on keeping goldfish as pets, especially as more and more countries are clamping down with laws around the way they are kept?

Yeah I'll add that keeping goldfish in a goldfish bowl is illegal in some parts of Europe. I think the city of Rome some time ago, Switzerland and the Netherlands may also have some other laws like that, as it should be.

I mean these are social animals, a goldfish can live 40 years, they can form social relationships, they’re renowned for helping others in distress - other goldfish who may be their friends in an aquarium situation, and this kind of thing probably happens in the wild as well. They like places to hide and the barren goldfish bowl has become something of a meme.

So you know it's a terrible fate for that fish who’s probably not going to live very long. Who knows whether they can die of depression or not, it wouldn't surprise me, but they certainly are probably miserable in that setting.

4. Do you think keeping fish in captivity helps people understand and relate to fishes?

There's a lot of problems with the aquarium fish industry and if I could snap my fingers and that whole dimension about our relationship with fishes went away I would. Just because of the terrible mortality rates, the harmful methods by which the fishes are caught and transported are inhumane and harmful and the death rate of very very high.

Having said that, that's not to say however that there aren't some salubrious aspects of the relationships that humans may have with aquarium fish. Many aquarists probably just feel proud to have them and they like to look at them and that’s it. But there are many who form relationships with their fishes and I describe some of those in my book What a Fish Knows. These are long-term, multi-year relationships, a decade or longer where these animals have names and they greet them when the human comes home, the fish comes to the tank to greet the human and they might play games.

One person actually would cup her hands and put them in the water and her blue discus fish, Jasper, would swim into her hands, lie on his side and she would stroke him with her thumbs and this became part of their connection. Needless to say she was very sad when he died, I mean people form these connections with these creatures.

So certainly that type of relationship can enhance our respect in relation to fishes but, unfortunately, it also happens as part of an exploitive, harmful industry to fishes so it's a bit of an irony in there.

5. What do you think is the best way to encourage empathy for fishes?

It's hard to say. I want to say if they learn all the facts about them, that they have emotions and they think and have social lives, etc, I think that's valuable. But time and again we hear that facts don't actually get people to change their minds nearly as much as feelings do. If you can touch them here, if you can engage their emotions with stories, stories can touch.

I've learnt as a science writer that it’s important to include stories - personal experiences but also those of others. So I think stories, if people read about what fishes are capable of doing in a story like touching context, might be effective.

Ironically it's often thought we need to get people to change attitudes and then they’ll stop eating them. Flip it around the other way - the biggest barrier to them changing may be that they’re eating them. So if people stopped eating them they no longer have this need to defend the behaviour, they no longer have this need to keep fishes at a distance to alienate from them. That's a very powerful cognitive dissonance kind of effect.

But of course, getting people to stop eating something that they’ve been eating all their lives and they considered benign to do so or they think it's acceptable or not willing to give up the taste - all these reasons we hear. It's very hard to do to get someone to give up something that is part of their life every week and they may have that common perception that they won't be able to replace that, even though as I say in my talks about fishes there are more and more products coming out.

The rise of plant-based meats and the rise of cell-cultured, lab-grown, clean meat, whatever you want to call it. I mean these could be game-changers. But getting people to stop eating them is the best thing we can do to improve our relationship with fishes ultimately.

6. Do you think there's a risk of alienating people when using new language like ‘fishes’?

Yeah the language to use is really important in how we convey messages about animals and how we may view them and our attitudes towards them.

It was quite early on in the process of researching and writing What a Fish Knows that I decided to advocate for calling them fishes instead of fish, the collective fish. And let me just say the word fishes is a legitimate word in the English language and its more formal use is to refer to more than one species of fish. Books about fishes, academic books and textbooks and such, always use the word fishes not fish so that word is very legitimate. It's just not usually used for individuals and I kind of made the case we should use it for individuals.

It's a bit of a risk to do that because one might be coming across as a big dogmatic, or maybe I should say fishmatic, about how we use language and how we name things. I actually got an email once from Peter Singer, maybe three or four years ago, saying I know you're advocating for fishes but it's a bit awkward and it makes us sound dogmatic, or something to that effect. And I somewhat relented, I said I hear you, I see what you saying and I’ve encountered that too.

Obviously, I'd say it's a judgement call depending on the audience and in the context of what we call them. If we are to say fishes in a context that might seem a little awkward, probably we need to go to the trouble of explaining why we think that might be a better way to call them. But you know you can get a little too tied in knots, it can get a little bit awkward if you were to say salmons and tunas. I've seen those words in the plural but it's not typical.

But isn’t it interesting that we use the singular and it kind of just homogenises them all. Ah they’re all the same, they’re all fish. They aren’t! They are totally unique, each species is different and every individual within the species. So, if nothing else, being dogmatic and saying fishes gets people talking about things that are worth talking about.

7. What made you want to write Super Fly?

Super Fly for those who may not know is an exploration of the lives of a group of insects that deserve some press and some attention: the flies, the true flies, the Diptera. They are so named because they have two wings and not the usual four among flying insects.

So they're diverse, incredibly successful - probably the most successful insects on earth. And insects already are far and away the most successful of the macroorganisms and ones that we can see, not counting microorganisms. 80% of all animal species on earth is an insect so that statistic alone supports what I just said.

Flies are arguably, and it's becoming more and more thought to be the case, the most diverse group within the insects. Beetles have been the leaders for decades but new discoveries of new species of beetles are much slower paced than new discoveries and new species of flies. It is thought that from the around 16000 species that we know now, there may be five times that many in the world. When entomologists go to the tropics and sample insects in their traps and they look at them, most of them are undescribed and certainly most of the flies have never been seen before.

There’s a sobering subtext to that, of course, that as we destroy a rainforest habitat we’re probably losing many species every day because some of these flies are very specialised and may have very small ranges so we’re losing species before we know they’re there. So diversity and success is one of the reasons why I wanted to write about flies.

We all have experience with flies. Mosquitoes are flies so unless you’ve stayed cloistered in your home all your life and even then you probably have had an experience with a mosquito. They’re omnipresent, there are several thousand species, most of which don't bite humans but there’s enough of them that bite to get our attention. And of course in tropical areas they can harbour very dangerous diseases. Mosquitoes are credited with killing more humans throughout history than humans have, which is the only species that ranks or only group of animals that ranks above us for killing our own species so that's pretty sobering fact.

But I didn't read the book to demonise insects. We need them, we need flies, we need insects because they are 80% of all animals. They are running the planet, we think we are but we are much more vulnerable than small creatures who can have 25 generations in one year. They are much more evolutionarily nimble. A million years after the last human treads the earth there will be a fly preening her wings on a leaf, hopefully on a leaf.

So we shouldn’t be too big for our boots when it comes to insects, we only think we're running the show here but actually the insects are.

So that's another reason why I wanted to write the book it to make people aware that we need them. Insect declines are disturbing as with fish declines. It’s estimated about half of all insects have disappeared from the planet in the last 50 years and they're ranked second only to the bees and wasp for pollination services. Pollination of plants of course is the food that we eat and even people who eat meat, the animals that they eat are herbivores and they need plants to feed themselves. So everybody ultimately relies on plants for our food supply

Plant-based fish options blog

Want to know about plant-based alternatives to eating fish? Read our blog to find out more.

Pru Elliott

Pru Elliott